Broadly speaking, our first camping episode was successful. Our dinnertime ratatouille was bland, our breakfast modest. Our campfire lasted long into the night, overseen by a couple of tuk-tuk guys who stayed overnight to insure our security. Given the amount of beer we downed maybe their security was more at risk than ours. Earlier in the afternoon we had a glorious swim in the swirling currents of the Betwa River, a welcome counter to the heat of the day. Despite cooler jungle air and my cold, we swam again before breakfast.

For the next 400 km. we continued to follow the rugged Vindhya range, dotted occasionally by dusty roadside settlements.

With the heat and the bumps, the trip did not register, neither in photos nor memory- except for probably our first crossing of a controlled provincial boundary, probably between Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. It is unusual elsewhere to encounter a rigorous border check-point between federal units-except maybe the fruit-check at the edge of Florida. But here, massive gates, a massive parking space filled with 18-wheelers, secure-looking buildings and scurrying agents. Not for the last time our truck-like appearance failed to convince the enforcers that we were just tourists, not some taxable commodity. Not for the last time Ali became our spokesperson, maybe in the hope that dealing with a woman would frazzle the enforcers into leniency. She had to march across the parking expanse with a load of papers to make our case. Took a good half -hour. We took the opportunity to have a pee.

The roads actually improving as we rolled westward towards Agra, we arrived around 3pm at the Hotel Dazzle, named thus to distract its guests. I think maybe we were its first guests ever: quite modern and comfortable building, but no keys to rooms, beds not made up, little toilet paper, many young boys hanging around aimlessly. Whenever one wanted to leave or enter a room, or get some TP, one of the boys had to be found and roused to action. On the location side, better news: good shopping and restaurants nearby including a British coffee chain. The addicts were saved. Some guys got shaves and haircuts, a very cheap luxury inaugurated earlier in the border town.

In the evening we visited Itmad-ud-Daulah tomb (sometimes known as the ‘Baby Taj’), and viewed the Taj itself from across the Yamuna River.

Next morning we were up again at 5 to visit the Taj Mahal. Due to bureaucracy we missed chance to see it in the light of a full moon. We were there to see it at sunrise but almost missed that too due to queues and incompetent guide.

An imposing building of solid white marble, the Taj was built by the fifth ruler of the Mughal empire, Shah Jahan. Begun in 1631 it took 20 years to complete, engaging over 20,000 workers and skilled craftsmen, some of whom were brought in from all over India, Central Asia and even Europe to work on the marble inlay work and complex decorations. The site has been described by UNESCO as being “the jewel of Muslim art in India and one of the universally admired masterpieces of the world’s heritage”. (Dragoman notes). A masterpiece of Islamic architecture, it was designed to commemorate the Shah’s favorite wife, Mumtaz Mahal.

The Mughal invasion…

Agra rose from obscurity in 1504 when Sikander, a dominant Lodi sultan based in Delhi proclaimed Agra as his alternate capital, building a fort to subdue the rival Tomar rajputs of Gwalior, a town just south of Agra. The Lodi people were Afghans who in 1451 succeeded the Saiyyids, another Afghan group who established themselves in Delhi after the sacking of the city in 1398 by the Central Asian warlord Timur (Tamburlaine). Successive waves of invaders, led by Turks, Persians and Afghans, sought the plunder offered by the resources and craftsmen of Hindu India. Though these Islamists largely tolerated Hindu practices, they instituted the jizya, a tax on its practioners.

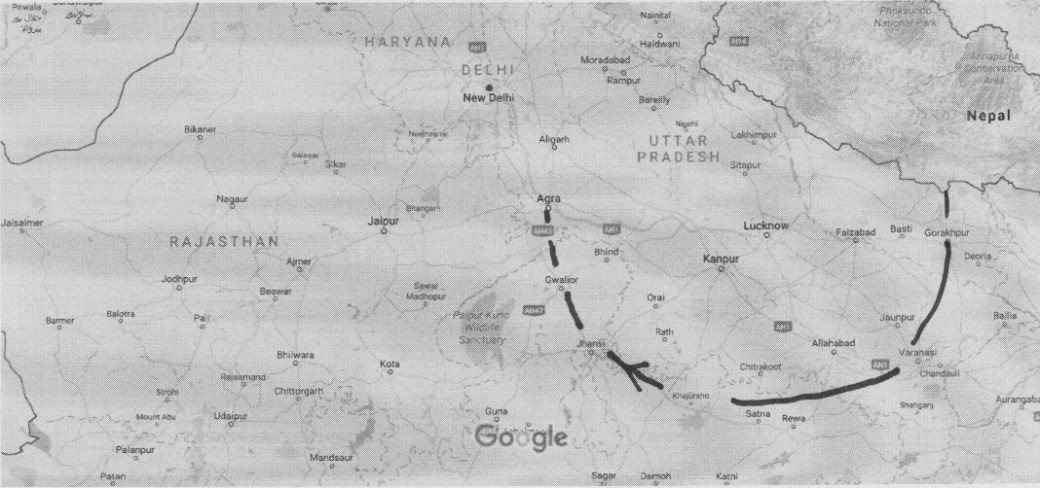

Northwest India, with our route to Agra among sites mentioned

In turn, the first Mughal (Mongol) khan, Zhar-ud-din Mohammad (1484-1530), known as Babur the Tiger, culminated a series of attacks on the Punjab from his base in Kabul by capturing Agra and Delhi in 1528. Babur was a distant descendant of Ghengis Khan originally form Tashkent. Significantly, he was a sensitive character given to artistic and poetic expression. Equally significantly, he mastered the use of new gunpowder technologies and thus overran the more numerous forces of Rana Sangha and other Punjab rajputs in Northern India in 1527-29. So began 200 years of Mughal rule in India.

Babur died in 1530, succeeded by his favorite son Humayun (1508-1556), more of an aesthete than a warrior, who nonethess managed to conquer much of Rajasthan, Malawa and Gujarat in the western Punjab over 1534-36. Gradually he frittered away these gains, ceding his kingdom in 1540 to another Afghan, Sur Shah Khan, the ruler of Bengal to the east. Though the Sur people ruled the Punjab for 15 years, Shah Khan died in 1545 during a successful attack on Kalinjar, the hill fort protecting Kajuraho, thus starting the famous temples’ disappearance into the jungle. Shah Khan in his brief reign initiated administrative reforms, including systematic revenue collection and military organization, that the Mughals later perfected.

After his defeat Humayun fled, eventually to Persia where, in return for the fabulous Khoh-i-nur diamond (186 karats) which he had obtained after conquering the raja Vikramaditya of Gwalior, he was given a largely Persian army. With it he reconquered the Punjab by 1555- then died accidentally from a fall from his makeshift astronomical observatory in Agra.

Humayun’s 12 year old son Akbar (1543-1605) succeeded him. Probably dyslectic, never able to read and write, Akbar showed promise as a warrior. Indeed, with the support of his able regent Bayram Khan he defeated the previously unbeaten and equally unlikely warrior of lowly origins, the Hindi Hemu, who could not even ride a horse but nonetheless swept the Mughals from Delhi shortly after Humayun’s death. Against a superior force including hundreds of elephants Akbar prevailed when the enemy panicked after their leader Hemu fell.

Akbar thus began his 50-year rule. In 1556-60 he defeated the Sur rajas in Punjab, Awadh, and Gwalior. In complete control at 19 years old, he engaged the local Hindi people and immersed himself cultural and religious issues. He enjoyed first-hand the diversity of his Indian countrymen, and lifted the detested jizya tax on non-Muslims. In 1562 he married the daughter of the raj of the Kacchwaha rajput of Amber, near where the Kacchwahas would later found the city of Jaipur, and wisely incorporated the raj and his family into the Mughal hierarchy as nobles (amirs). By creating bonds with rajas throughout Rajasthan, allowing them to retain their assets and privileges, Akbar gained their allegiance as well as their considerable armies.

At this time Akbar completed the great Red Fort on the banks of the Jamuna in Agra. Together with strongholds at Lahore, Allahabad and Ajmer, Agra formed the foundation of the Mughal empire in northern India. As it happened, Akbar’s first son Jahangir was born in nearby Sikri in 1569. Viewing this as auspicious, Akbar decided to build a new capital there, renaming it Fatepur Sikri (next stop on our trip). In this new capital he plunged deeply into religious issues, inviting members of a wide range of beliefs into debate, culminating in the creation of a “Divine Faith” centred on himself- though he did not view himself as a deity.

In 1585 Akbar, having subdued Rajasthan, Gujarat, Orissa and Bengal in the east, again moved his base, to Lahore, to focus on the northwest frontier, where he secured Kashmir, Sind, Kabul and Kandahar. Only the Deccan and the south remained outside his reign- so in 1598 he returned to Agra to tackle the nearest Deccan sultanate, perhaps feeling secure in the Red Fort from both his southern enemies and his increasingly powerful son Jahangir.

In fact Jahangir (1569-1627) seized the throne in 1600 during his father’s absence in the Deccan, and in 1602 declared himself emperor. Reconciled with his father before Akbar’s death in 1605, he secured his succession by blinding a more popular rival- his own son. “A king should deem no man his relation” he said. Sure enough, in 1622 Jahangir’s favorite son, on whom he had just bestowed the title ‘Shah Jahan’ (King of the World) murdered the blind brother and rebelled against his father. Reconciled with his father just before the latter’s death in 1627, Shan Jahan killed the remaining brother and other possible pretenders.

During his father’s reign Shah Jahan ( 1592 -1666) made a number of conquests, principally against the Mewar rajputs to the south, and less impressively the fort at Kangra in the Himalayan foothills, areas around Kashmir and the minor hill-state of Garhwal. On the other hand, he failed to halt incursions in Bengal in the east and Afghanistan in the west. Later, as emperor, Jahan was more successful in forcing the realms of Golconda and Bijaour, further south, to submit as vassal states. These states eventually extended by force Mughal dominion into Tamil Nadu and Madras, still further south. So Shah Jahan in the end controlled much of what is modern India.

However, Shah Jahan is mostly remembered for what he built: completion of the Red Fort in Agra, another Red Fort in Delhi, Shalimar Gardens in Kashmir, a palace in Ajmer, mosques in Lahore, his father’s tomb in Lahore, a whole new city Shahjahanabad (now Old Delhi) and of course the Taj Mahal. Jahan had married one of his mother’s nieces, Mumtgaz Mahal (roughly, ‘Palace Favorite’). After she died in 1631 giving birth to a 14th child (surprise!) the distraught Jahan began in the following year the construction of her tomb- the Taj Mahal, a masterpiece combining Muslim architecture with Indian design and craftsmenship. It integrates features of Humayun’s tomb (Akbar’s work), the inlaid marble of the tomb of Jahan’s father-in-law Itmad-ud-Daulah ( by his wife), the spectacle of Akbar’s tomb (Jahangir) and the landscaping of Jahangir’s gardens.

Classical Mughal architecture, majestically combining Islamic and Indian features, realized in the Taj, symbolizes the broader efforts of the Mughals to synthesize Islamic and Indian traditions to gain the support of their Hindu subjects. Another aspect of this initiative was the growth, in the same period, of the Urdu language, a hybrid rooted in the patois of military camps.

This long digression on the first five of the Mughal emperors sets the scene for the magnificence of the Taj Mahal and the red fort in Agra. From its gates the Taj announces itself as a special monument.

The tranquil mall invites us for a closer look…

Impressive engraving and paintings adorn both the exterior and interior walls of the Taj…

From the tombs of Shan Jahan and his wife Mumtaz Mahal, to the living…

The Marble Works

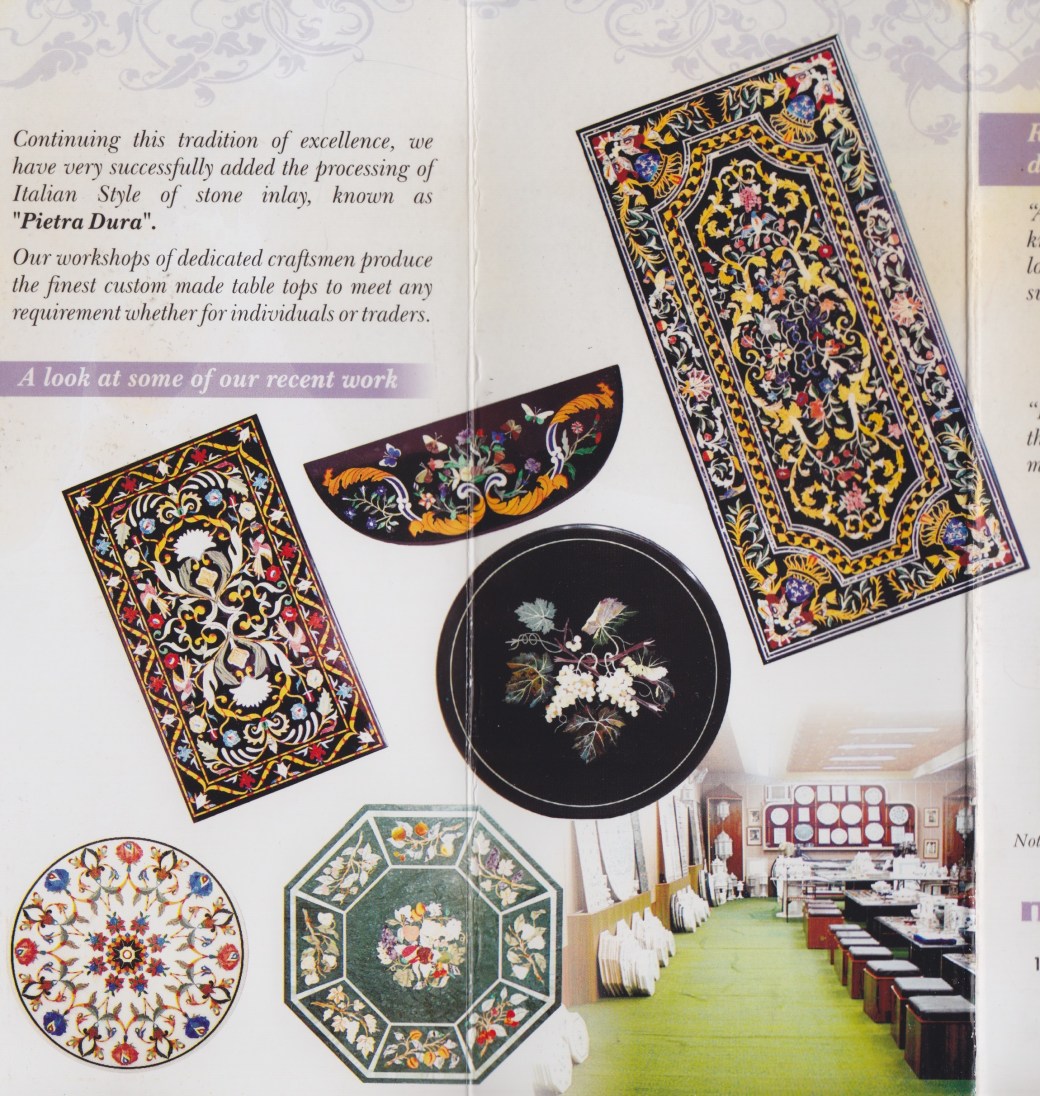

After our earlier morning visit to the Taj the tuk-tuks took us to a marble studio in central Agra, to see modern craftsmen creating the sorts of artistry we saw on the walls of that monument to Mumtaz. In this case the creations are more mobile- from small statues through wall hangings to large tables. In the studio’s anteroom we introduced by its director to a form of art new to me, inlaid marble. Formally called Pachchekaari, a Persian term for “marquetry with gem stones” on marble, the craft dates from the Mughal era., revived by the founder of this studio in the early 20th century. I was impressed by his business ethic, displayed in two plaques on the walls: value your customers, they are your life read one; the other urged ‘value your employees, they are your best asset’. Unfortunately, we were unable to photograph the magnificent pieces in the adjoining room- copyright concerns I suppose- but we did see a sample of the craftsmen at work.

Using some pretty ancient looking tools, the artists are etching wonderful patterns into marble surfaces, then inserting almost invisible shards of precious stones into the grooves.

Design for a new pattern.

Etching phase, on a small decorative plate.

Steps in the production of the final artifact.

Though we were unable to photograph the extraordinary collection in the very large showroom, a couple of captures from the firm’s brochure suggest the intricacy and colourfulness of the designs and the range of objects on which they can be realized.

Fortunately, I did not have 13,000 pounds sterling in my pocket- otherwise I would have come home with an absolutely gorgeously patterned dining table for eight…

Brunch

After the Marble Emporium we adjourned for a much-delayed breakfast at our guide’s home.

Like many things in India, worth the wait.

A delightful brunch prepared by the host’s family.

Not sure if the many lovely ladies are daughters or alternate wives. In any case, totally charming.

As we ate, a few local monkeys (literally) bounded about the rooftops. Too quick for a photo, but I did capture a local ironworks operating in the street below, quite typical of the very low key, low tech industries practiced on the streets throughout India. The woman is powering the ‘blast furnace’ while the guys are shaping the molten metal.

The Red Fort in Agra

Next on our agenda, the Red Fort, started by Akbar in 1562 as he established his capital in Agra. We spent most of the afternoon in this immense (96 acres) sandstone stronghold.

Like other bastions of power in India, the fort is remarkable not only for its gigantic external battlements but also for the beauty of its interior…

and especially the beauty of the enclosed palace, where the Mughal emperor lived with his wives and harem

The palace contained an innovative early air conditioning system, cooling water pouring hollow walls in the main chambers. Not quite automatic- the water was hauled to the roof by a gang of minions.

Typical palace features, an ornate dais for audiences with ministers or the public…

and a mosque.

Following the established practice, Shah Jahan was deposed by his son Aurangzeb (1618-1707) in 1658. It is speculated that a main reason for the coup was the decline of the empire’s economic health, exacerbated by the immense cost of the construction of the Taj Mahal. Shah Jahan was imprisoned in the palace of his red Fort until his death in 1666. Ironically from the walls of his not incommodious prison he could gaze wistfully at the Taj…

where he eventually joined his beloved wife in death.

Postscript

The death of Aurangzeb, the last of the great Mughal emperors, in 1707 began the decline of the empire, which petered out by 1857, with the exile of the last Mughal, Bahadur Shah Zafar (Bahadur Shah II) after the British retook his retreat, the Red Fort in Delhi. The reign of the Mughals outlined here could serve as the paradigm of governance by local chieftains throughout India before the coming of the British, first with their East India Company and later with political conquest, culminating in the final annexations of territory and suppression of the ‘Great Rebellion’ in 1858. On the one hand there was the Mughals’ superior military skill, not in massed numbers but in the mastery of technologies like gunpowder and above all, tactics. On the other hand, the Mughals like those before them amassed enormous wealth through plunder and taxes on the masses which they turned into colossal fortifications, palaces and temples.

On the good side, the repeated invasions from the east, Persians, Central Asians, Afghanis, and Mongols, seeking to plunder “Hindustan’s” resources and arts, brought new technologies, languages, literature, religions, and forms of governance, and especially in the case of the Mughal emperors, a deep interest in philosophy, science and astronomy.

On the downside, building empire meant the shedding of a lot of blood, not just of rival pretenders but tens of thousands of captives, sometimes whole cities. For example, the intellectually enlightened Akbar nonetheless massacred 20,00 after ending the siege of Chitor.

The legacy we see, immense fortresses, magnificent palaces constructed with thousands of tons of sandstone and marble imported some times from great distance undoubtedly cost thousands more lives of humble workers or slaves. Astounding wealth accumulated in a few hands, at great expense to the struggling masses. But lest we become too smug about our own story, note that we are not far removed from our own feudal state. Witness, as a random example, Arundel Castle.

Same scale. Same source: taxes on struggling tenant farmers

And though the tide has raised us all since then, the proportional share of total wealth is probably about the same.

Back on the road

Next, we head for Jaipur, the “Pink City”, by way of Fatehpur Sikri.

Note: The historical background here and elsewhere is largely drawn from John Keay’s really excellent, highly readable India, Harper Press, updated 2010.